Chapter Thirty

The Author is faced with crucial decisions concerning her future, now that she has resigned to the fact that her Husband is dead; Still, she decides to complete the narrative of her brave Husband’s story of two years past, before she drops the Quill for good; Gulliver is faced with mortal dangers and manages to escape from Lilliput, in a tour-de-force of saving the Blefuscudians; He arrives safely in London, but leaves his loving family after a few months, never to return; Probably lost at sea. Surely lost.

Redriff, Tuesday the 28th of December, 1703

THIS will be the last time I write my memories, and Lemuel’s.

I have matured.

I understand that my hopes of ever seeing my Lemuel again are but a folly. Stella is right. I must accept the reality of my life, and resolve to dedicate it to the happiness of my surviving children.

These are days of making resolutions, and this one is mine: I will always love my Lemuel, but I will also abandon the foolish hope of his ever returning safely from his last voyage. I thank the fates for having brought him back to me from Lilliput, but I accept that the voyage he took next, was indeed his last.

I will never see him -- again.

I have to stop crying. Tears will help me not. Stella is right. I should sell this house, our Redriff love-nest, and repair to return to my childhood home with Johnny and Betty. It is a big house, and since the hosiery business is expanding, Mr. Owen Lavender Jr. resolved to take on a workshop nearby. Stella will furnish it to accommodate my little family. Johnny is big enough to work and he will join the family’s business. Betty will take care of me in my last years. I fear I will not live now much longer, with this broken heart of mine.

The story of Lemuel in Lilliput is also drawing to a close. These will be the last ink marks I will ever apply to paper:

*

IF Lemuel thought that his relationship with the Empress had taken a new turn, after their nightly encounter in the fields, and that now he would be favored in Court, he was miserably mistaken.

If anything, it seemed as if she now openly detested him to no extent and never lost an opportunity to express it.

Reldresal was eagerly confiding in Lemuel all that which had transpired in Court, and with each new token of hatred of Her Majesty, Lemuel felt that another Lilliputian poisoned arrow stung his heart.

In the days that followed Lemuel was using any excuse to postpone accomplishing the mission he was given, to steal the rest of the Blefuscudian ships, kidnap their King and Court, to enable the Lilliputian monarch to conquer and occupy Blefuscu and its people.

As all dignitaries but Reldresal were too dignified to be seen with him, following his infamous fire extinguishing, it was not that difficult to avoid complying with the draft he was given, and Lemuel was hoping that given time, this indignation of his would pass away.

His only consolation was, that he was nightly requested to accomplish far more Lilliputian matrimonial obligations than ever before.

A fortnight after that fateful meeting with the Empress, Lemuel was woken up in his Freedom-Temple, and when he opened the gate, he saw but a Close Chair, carried by two chairmen. They did not wear any uniforms, so Lemuel could not detect who was the Noble Person inside the Close Chair.

His heart missed a beat when he saw the chairmen retreating respectfully to wait outside.

With shaking hands Lemuel picked up the Chair and brought it inside his Temple, but was he ever disappointed when it was not the Empress who stepped out. He was still hoping that she would come to her senses and for another night of passionate lovemaking.

But it was Reldresal who emerged from the Close Chair. He came to see Lemuel clandestinely. After the common salutations were over, Reldresal desired that Lemuel would hear him with patience, in a matter that highly concerned Gulliver’s honour and his life.

“You are to know,” said Reldresal, “that several committees of council have been lately called, in the most private manner, on your account; and it is but two days since his Majesty and his Empress came to a full resolution.

“You are very sensible that Skyresh Bolgolam has been your mortal enemy, almost ever since your arrival. His original reasons I know not; but his hatred is increased since your great success against Blefuscu, by which his glory as admiral is much obscured.

"This lord, in conjunction with Flimnap the high-treasurer (whose enmity against you is notorious on account of his lady,) Limtoc the general, Lalcon the chamberlain, and Balmuff the grand justiciary, have prepared articles of impeachment against you, for treason, future treason and other capital crimes. I procured information of the whole proceedings, and a copy of the articles; wherein I ventured my head for your service.”

“I am ever at your debt.” Said Lemuel, extremely worried.

“No need to thank me” Said Reldresal, very earnestly. “Our relationship is sacred to me, and I will risk my life to save yours. Our fates are intertwined.”

And he handed the document to Lemuel, but of course, Lemuel could not read that little print, and Reldresal went on to read the ‘Articles of Impeachment against QUINBUS FLESTRIN, (the Man-Mountain:)

ARTICLE I.

“Whereas, by a statute made in the reign of his Imperial Majesty Calin Deffar Plune, it is enacted, that, whoever shall make water within the precincts of the Royal Palace, shall be liable to the pains and penalties of high-treason; notwithstanding, the said Man-Mountain, in open breach of the said law, under colour of extinguishing the fire kindled in the apartment of His Majesty’s most dear Imperial Wife, did maliciously, traitorously, and devilishly, by discharge of his urine, put out the said fire kindled in the said apartment, lying and being within the precincts of the said Royal Palace, against the statute in that case provided, etc. against the duty, etc.

ARTICLE II.

“That the said Man-Mountain, having brought the imperial fleet of Blefuscu into the royal port, and being afterwards commanded by his Imperial Majesty to seize all the other ships of the said empire of Blefuscu, and reduce that empire to a province, to be governed by a viceroy from hence, and to destroy and put to death, not only all the Big-endian exiles, but likewise all the people of that empire who would not immediately forsake the Big-endian heresy, he, the said Man-Mountain, like a false traitor against his most auspicious, serene, Imperial Majesty, did petition to be excused from the said service, upon pretence of unwillingness to force his consciences, to destroy the liberties and lives of an 'innocent' people. Even though the Man-Mountain relented to do his duty to his Emperor, he seems to be avoiding it and there is ground to suspect that he will be bold enough to betray the Emperor's benevolence and there is even ground to suspect that the Man-Mountain will defect and will join our mortal enemies, the Blefuscudians.”

Reldresal rolled up the parchment.

“.. My oh my... ” Indeed, Lemuel was gravely concerned. This did not bode well.

“There is one more point," continues Reldresal, very earnestly, "which seems to underlay all these manoeuvres, and this is, that our cannibacea fields are ready to be harvested, and there are rumours that a number of secret, powerful players, are pressing to smuggle and sell all of the crop to Blefuscu, before you annihilate them all, or else we rob ourselves of that market."

"Is that it?," Lemuel was lost for words "Is it all about the income from smuggling, which, I am privy to the knowledge, is always deficient?"

"How do you know that?" Reldresal's ears perked.

"They told me all" Lemuel said "The Blefuscudians collaborate with your smuggling bands, that collaborate with each other. If you, the lords of this country, would trust each other and tend to your own people rather than to your own pockets, you would not be so easily fooled by the ingenuity of your hired criminals."

"My dear Little Huggy Haggy Boar,״ Reldresal could not hide his sarcasm: "You have a most unfortunate misunderstanding of Politics, and I cannot fathom how to begin educating you. In any case, it is too late now. I spared some other articles from you, but these are the most important, of which I have read you an abstract. And your fate is not rosy.”

“So, what will become of me?” Lemuel’s voice quivered.

“In the several debates upon this impeachment,” Reldresal was choosing his words carefully, “it must be confessed that His Majesty gave many marks of his great lenity; often urging the services you had done him, and endeavouring to extenuate your crimes.”

“And the Empress, what did she say?”

“Nothing. But the treasurer and admiral insisted that you should be put to the most painful and ignominious death, by putting you on a strict non-Glimigrim diet for a few days and then setting fire to your house at night, and the general was to attend with twenty thousand men, armed with poisoned arrows, to shoot you on the face and hands upon your emergence from within."

"Oh" was all Lemuel could utter.

"Some of your servants were to have private orders to strew a poisonous juice on your shirts and sheets, which would soon make you tear your own flesh, and die in the utmost torture. "

"Oh"

"The general came into the same opinion; so that for a long time there was a majority against you; but His Majesty resolving, if possible, to spare your life, was unfortunately outflanked by the chamberlain."

"Oh"

“Upon this incident, I, Reldresal, principal secretary for private affairs, who always proved himself your true friend, was commanded by the Emperor to deliver my opinion, which I accordingly did.”

“And what did you say?” Lemuel was desperate “What could you possibly say?”

“I did justify the good thoughts you have of me, my dear Huggy Haggy Boar.” Reldresal blew a kiss at Lemuel’s direction, which did not cheer Lemuel up at all. “I allowed your crimes to be great, but that still there was room for mercy, the most commendable virtue in a Prince, and for which His Majesty was so justly celebrated."

"Well done, old chap!" For the first time Lemuel thought he had reason for hope.

"I said, that the friendship between you and me was so well known to the world, that perhaps the most honourable board might think me partial; however, in obedience to the command I had received, I would freely offer my sentiments."

"Which were....?" Lemuel was getting excited, sensing rescue on the horizon.

"That if His Majesty, in consideration of your services, and pursuant to His own merciful disposition, would please to spare your life, and only give orders to put out both your eyes, I would humbly conceive that, by this expedient, justice might in some measure be satisfied, and all the world would applaud the lenity of the Emperor, as well as the fair and generous proceedings of those who have the honour to be his counsellors."

"Oh..."

"That the loss of your eyes would be no impediment to your bodily strength, by which you might still be useful to His Majesty (and may I add now, between you and me, dear Boar, your bodily virtues would still be useful for us.)”

“I dare say..” Mumbled Lemuel, aghast.

“And you are right, my dear! I knew you would see eye to eye with me! Blindness is an addition to courage, by concealing dangers from us; Poking out but your two eyes would be sufficient in the eyes of the ministers, since the greatest Princes do no more.”

“I hope this idea was not too popular.” Whispered Lemuel.

“Oh, This proposal was received with the utmost disapprobation by the whole board.” Said Reldresal to Lemuel’s relief. “Bolgolam, the admiral, could not preserve his temper, but, rising up in fury, said, he wondered how I durst presume to give my opinion for preserving the life of a traitor; that the services you had performed were, by all true reasons of state, the great aggravation of your crimes; that you, who were able to extinguish the fire by discharge of urine in Her Majesty’s apartment (which he mentioned with horror), might, at another time, raise an inundation by the same means, to drown the whole Palace.”

“Only if it will go up in flames..!” ventured Lemuel, helplessly.

“Bolgolam shrewdly suspected that the same strength which enabled you to bring over the enemy’s fleet, might serve, upon the first discontent, to carry it back; that he had good reasons to think you were a Big-endian in your heart; and, as treason begins in the heart, before it appears in overt-acts, so he accused you as a traitor on that account, and therefore insisted you should be put to death.”

“He never liked me too much,” said Lemuel. “But, were there no sane voices speaking up for me, beside yourself? What did Her Royal Highness, the Empress, say?”

Reldresal ignored the question. He just went on to count Lemuel’s enemies: “The treasurer was of the same opinion: he showed to what straits His Majesty’s revenue was reduced, by the charge of maintaining you, which would soon grow insupportable; that the secretary’s expedient of putting out your eyes, was so far from being a remedy against this evil, that it would probably increase it.”

“Thank heavens,” sighed Lemuel. “I always knew that Flimnap had more sense in him than to suspect me of having an affair with his wife! Jolly good fellow, Flimnap the Treasurer! And what did the Empress, Her Highness, say?”

“Well,” Reldresal was trying to avoid Lemuel’s eyes. “Flimnap said that His Sacred Majesty and the council, who are your judges, were, in their own consciences, fully convinced of your guilt, which was a sufficient argument to condemn you to death, even without the formal proofs required by the strict letter of the law.”

“What shall I do..? What shall I do? What did the Empress say? Pray, tell me, Reldresal, you are my friend, after all. Are you not?”

“Of course I am,” said Reldresal, “And will always be. His Imperial Majesty, fully determined against capital punishment, was graciously pleased to say, that since the council thought the loss of your eyes too easy a censure, some other way might be inflicted hereafter."

"I dare not imagine what that would be." Lemuel was beginning to sweat.

"And then I, your friend, the secretary, humbly desiring to be heard again, in answer to what the treasurer had objected, concerning the great charge his majesty was at in maintaining you, I said, that His Excellency, who had the sole disposal of the emperor’s revenue, might easily provide against that evil, by gradually lessening your establishment; by which, for want of sufficient food, you would grow weak and faint, and lose your appetite, and consequently, decay, and consume in a few months; neither would the stench of your carcass be then so dangerous, when it should become more than half diminished; and immediately upon your death five or six thousand of His Majesty’s subjects might, in two or three days, cut your flesh from your bones, take it away by cart-loads, and bury it in distant parts, to prevent infection, leaving the skeleton as a monument of admiration to posterity, against a visit-fee, of course.”

“Of course..?” Lemuel was thinking hard.

“Thus,” triumphed Reldresal, “by the great friendship of your friend, I, the secretary, the whole affair was compromised. It was strictly enjoined, that the project of starving you by degrees should be kept a secret; but the sentence of putting out your eyes was entered on the books; none dissenting, except Bolgolam the admiral, who, being a creature of the Empress –“

“Yes” Lemuel cut Reldresal short “what did the Empress say?”

“Well, Bolgolam was perpetually instigated by Her Majesty to insist upon your death, She having borne perpetual malice against you, on account of that infamous and illegal method you took to extinguish the fire in Her apartment.”

“I thought she forgave me.” Lemuel was crestfallen. “I thought she even liked it..” He mumbled to himself, but Reldresal heard him.

“Have you lost your mind with fear? Are you not a Man? How could you even think that Her Royal Highness liked... well, it...!”

“Sorry,” said Lemuel, realising that he disclosed too much. “You are right. I am despicable. Perhaps I should have all my organs pulled out. It would be a quicker death, if not less painful.”

“Courage, my friend!” Exclaimed Reldresal “Not all is yet lost!”

“It is not?” Lemuel could not hide his skepticism.

“Of course not,” Reldresal was jumping of joy, having apparently reached the best part of his narrative. “In three days, I, your friend the secretary, will be directed to come to your house, and read before you these articles of impeachment; and then to signify the great lenity and favour of his majesty and council, whereby you are only condemned to the loss of your eyes, which his majesty does not question you will gratefully and humbly submit to; and twenty of his majesty’s surgeons will attend, in order to see the operation well performed, by discharging very sharp-pointed arrows into the balls of your eyes, as you lie on the ground.”

“And this is a good thing, because..?” ventured Lemuel, desperately trying to understand.

“We will elope, my dear friend, my true love, my dear Huggy Haggy Boar!” exclaimed Reldresal enthusiastically.

“Elope?! Where to?!”

“Oh, my dear, you have no notion of your powers, that is so clear, and so endearing! I will sit on your head and you will swim back to your country, to Ingland, about which you told me so many wonders! We will live together, happy for ever after!”

“What a preposterous idea” said Lemuel, knowing that his days were numbered if this was Reldresal's solution. “Do understand me right, my dear little fellow. I love and cherish you as ever a man cherished a LOL, but I could never swim back home. It is too far away.”

“We have a three days’ window of opportunity.” Pressed Reldresal on. “I was directed to come to your house, in three days time and read before you the articles of impeachment. Then very sharp-pointed arrows would be discharged into the balls of your eyes and then, the general idea was to starve you to death!”

“In three days time…” mumbled Lemuel, deep in thoughts.

“If you will not elope with me to Ingland, I will bear this as a LOL. I will survive. But for our love’s sake, I will stick my neck out to delay the execution as long as possible.” Reldresal said resolutely. “So this is probably the last time I will see you, dear Huggy Haggy, and we do not have time for one last lovemaking. Your life is at stake. So I leave to your prudence what measures you will take, but pray, take them right away." And he sniffed.

"Yes. Yes. Of course" But Lemuel had no idea what to do. Not just yet.

"Oh. One last thing. I made sure to nip from the Palace archives the box marked “Quinbus Flestrin.” Get rid of it as soon as you can, in any manner you see fit. It is full of incriminating evidences against you.” Reldresal sniffed again. “To avoid suspicion, I must immediately return in as private a manner as I came.”

Reldresal did so; and Lemuel remained alone, under many doubts and perplexities of mind.

But by and by he fixed upon a resolution, and having his Imperial Majesty’s license to rob the rest of Blefuscu’s fleet, Lemuel took this opportunity, that very night, to send an official letter to his friend the secretary, Reldresal, signifying his plan to set out that very morning for Blefuscu, pursuant to the leave he had got; and without waiting for an answer, he went to that side of the island where the Lilliputian fleet lay.

There was no one in sight. The Lilliputian Navy was under the impression that there are no enemies left to mighty Lilliput, and the ships were not manned any more.

Under the blanket of a starless sky, Lemuel raised the anchors of six of the eight Men of War which lay in the bay and stealthily slid them out of the harbour. He resolved not to take all the Lilliputian fleet, for fear that Blogolam would immediately understand that Lemuel decided to escape, and in the process to rob all of the Lilliputian Men of War, to prevent Blogolam from chasing him.

No one noticed how he circled to the shores of Lilliput, where the fields of cannabaceae stretched wide, in full bloom.

Proud of his ingenious plan, Lemuel hastened to harvest as many plants as he could and stuff the handfuls into the ship holds, pressing down to squeeze more and more in.

Remembering that the Blefuscudian soil was not fit to grow cannabaceae, Lemuel dug dirt from the fields and loaded a few ships with soil only.

At high tide, nearing exhaustion, Lemuel swam back to Blefuscu.

That was his finest moment, he told me, when the sun rose and the grateful Blefuscudians realised what an immense service he had done them.

While they hastened to unload the ships, spread the soil and plant the seeds they found, Lemuel sauntered off to relieve himself of his own fertile soil mix in a not too distant valley.

Upon his return he suggested that the Blefuscudian cannabaceae fields will be refreshed from time to time with samples from the deposit he left in the valley.

The free-from-this moment-on-people of Blefuscu vowed eternal gratitude to Lemuel, but they were soon disappointed to hear that Lemuel was not intending to stay. He told them about the forces plotting his immediate demise at the Lilliputian court, and stressed that he only had a few days time, perhaps a week, before his enemies would grasp that he deserted them. Lemuel calculated that it would take a few months for the Lilliputians to build enough Men of War to ship all of their army over to Blefuscu, to hunt Lemuel down and execute him. Lemuel could not help thinking that some at the Lilliputian Court would be relieved to have his carcass rot on Blefuscudian soil, rather than on Lilliputian soil.

"Yours and my only salvation," Lemuel told the horrified Blefuscudians, "is that I will be gone, so that the Lilliputians will not be able to kill me here."

Some voiced the idea that Lemuel's presence in Blefuscu might be a deterrent for the Lilliputians to ever set foot in blefuscu, but others said, more judiciously, that the Lilliputian Emperor is not known to think straight, and he might resort to venomous vengeance, just for spite. Thus settled, Lemuel begged them to help him scout for any form of vessel they might spot on the ocean, north of Blefuscu, so he could escape.

They all went scouting, and lo and behold – that same day they spotted about half a league off in the sea, something that looked like a boat overturned!

Lemuel pulled off his shoes and stockings, and, wailing two or three hundred yards, he found the object to approach nearer by force of the tide; and then plainly saw it to be a real boat, which he supposed might by some tempest have been driven from a ship.

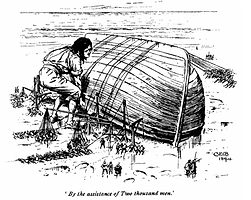

With the help of the Blefuscudian fishermen, the wind, the tide, and his own manly force, Lemuel got the boat to shore, and by the assistance of two thousand men, with ropes and engines, he made a shift to turn it on its bottom, and found it was but little damaged.

It did not take long to get it ready to sail again. The next two days were declared days of emergency. No cannabaceae was consumed and no love was for the making. Everybody worked hard, to save Lemuel, and themselves.

Five hundred workmen were employed to make two sails to the boat, by quilting thirteen folds of their strongest linen together. A great stone that Lemuel happened to find, after a long search, by the seashore, served him for an anchor. He had the tallow of three hundred cows, for greasing the boat, and other uses. He was at incredible pains in cutting down some of the largest timber-trees, for oars and masts, wherein he was, however, much assisted by the Blefuscudian ship-carpenters, who helped him in smoothing them, after he had done the rough work.

They all worked day and night, and Lemuel was nearly ready to sail, when word came - via the Cannabaceae smugglers - that the Lilliputian Emperor and His Court were suspecting something.

The Cannabaceae smugglers brought the latest gossip from court, that Reldresal was insisting that Lemuel would soon be back with the rest of the captured Blefuscudian fleet, and when that took too long to transpire, he himself was suspected of treason. Then Bolgolam, Shumclum and even the Empress insisted that Reldresal should get the punishment which eluded Lemuel. To prove his innocence as well as his loyalty, brave Reldresal volunteered to cross the channel by boat, all by himself, to avenge Lemuel singlehandedly.

But Bolgolam insisted that he was the one to lead the whole of Lilliputian fleet to attack and annihilate Blefuscu, including the Man-Mountain. The upside of the plan, they said, as Lemuel wisely deducted, that the Man-Mountain's carcass would then be left to rot on Blefuscudian soil, sparing the Lilliputians from stench and plague.

Having heard all that, Lemuel advised the Blefuscudians to leak the information via the smugglers, that Gulliver had resolved to stay in Blefuscu and defend it till his last drop of blood. “Tell them that my last drop of blood will be shed only after the last Lilliputian invaders’ drops of blood would be shed, so there.”

My wise man trusted that the Lilliputians would never dare attack Blefuscu, once they realised that Lemuel was resolute in taking the Blefuscudian side. He hoped that the Lilliputians would never learn of his departure, and, fearing confronting him on the battle-field, would resort to keeping the lucrative state of affairs with Blefuscu.

And thus, he quickly stored the boat with the carcasses of a hundred oxen, and three hundred sheep, with bread and drink proportionable, and as much meat ready dressed as four hundred cooks could provide within a few hours. He took with him six cows and two bulls alive, with as many ewes and rams, intending to carry them back home, and propagate the breed. And to feed them on board, he had a good bundle of hay, and a bag of corn.

A number of the Blefuscudians begged to join him, to entwine their fate with his, but this was a thing he would by no means permit, fearing they would be ill-treated in England, or anywhere else in the known world, for that matter.

In tears of sorrow and gratitude, the Blefuscudians waved Lemuel good-bye as he pushed his vessel onto the sea, jumped into it, and sailed away. Lemuel’s eyesight was bleary, too, from his own tears of gratitude, love and fear of what was to become of him.

He resolved to die as far away from Blefuscu as possible, hoping that with this heroic action he would preserve their lifestyle of loving and peace.

But fates decided otherwise, both for Lemuel and the poor Blefuscudians (as I heard from the refugees Biddle smuggled into England.)

When he had by his computation made twenty-four leagues from Blefuscu, he descried a sail steering to the south-east; He hailed her, but could get no answer; yet he found he gained upon her, for the wind slackened. Lemuel made all the sail he could, and in half an hour she spied him, then hung out her ancient, and discharged a gun.

It is not easy to express the joy he was in, upon the unexpected hope of once more seeing his beloved country, and the dear pledges he left in it.

The ship slackened her sails, and he came up with her between five and six in the evening, two years ago, on September 26th, the year 1701; but his heart leaped within him to see her English colours. Lemuel put his cows and sheep into his coat-pockets, and got on board with all his little cargo of provisions.

Well, the rest is history: the captain, Mr. John Biddel, seemed at first to be a very civil man. He treated Lemuel with kindness, and desired he would let him know what place he came from last.

Lemuel obliged him in a few words, but Biddel thought Lemuel was raving, and that the dangers Lemuel underwent had disturbed his head; whereupon my unsuspecting Lemuel took his cattle and sheep out of his pocket, and these, after great astonishment, clearly convinced Biddel of Lemuel’s veracity, and gullibility.

Six months later they arrived in England, and two months later Lemuel went back to sea, for the very last time.

*

And now, a year and a half since I last saw my love, I have resigned to the fact that, yes, it was the last time I was ever to see him.

And so,

I conclude this book, the stories of our lives,

With a deep sigh.

The End

Mary wipes her tears and gets ready to face reality.

Artist: Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre (1714-1789)

Lemuel and Reldresal in a secret audience.

Artist: Unknown

Skeptics listen to Reldresal's petitioning the Emperor to settle for poking Lemuel's eyes.

Artist: Grandville (1803-1847)

The emotional departure of Gulliver from Blefuscu.

Artist: Unknown

Reldresal trying to convince the assembly to settle for starving Lemuel to death.

Artist: Grandville (1803-1847)

Treacherous Captain Biddel sees a great opportunity in Lilliputian trade.

Artist: Unknown

Lemuel cannot believe what is in store for him.

Artist: Grandville